2008: Crash, Bank, Wallop

Before we dive into the intricacies of this complexity, let's talk about houses. Most of the times, people

borrow money from the bank or lending firms in vast amounts to secure the purchase and ownership of a new house, otherwise known as a mortgage. Naturally, the new homeowner is required to pay back the loan over a several year fixture, repaying small deposits on a monthly basis with added interest to the overall loan. All things good, the homeowner will, one day, clear all of their debts, and the lenders of the vast sum of money will have made up all of the money they gave out, plus the added interest in the form of profit. However, if the owner of the house is unable to pay back the loan and decides to stop paying altogether, it results in a default, in which case the mortgage lender will take the property from the person, and take ownership of it instead. This therefore results in lenders being a bit more hesitant to loan people with a poor credit score or low income, as they fear the risk of not being able to make up the whole loan, resulting in higher levels of defaulting.

During the mid 2000s in the US, investors discovered that the prices of real estate was increasing rapidly, due to the increased demand of housing property. This made the return on investment in the housing property market seem a lot more attractive than bonds. Investors turned their attention to the world of mortgaging: if they could distribute more mortgages, they knew they would be able to make a significant profit as they could charge higher interests on the loans, capitalising on the high demand for a house at the time. However, managing individual mortgages seemed far to cumbersome and administratively challenging, so large fiscal firms decided to group several mortgage loans together and distribute them - these ensembles of mortgages were called mortgage backed securities, or MBS. At the outset, this seemed like the eureka moment that would ignite the inception of a more lucrative market of mortgages and interests. An MBS would mean dealing with more mortgages at a time, ultimately leading to higher profit returns in the form of interest. The demand for MBS by investors sky-rocketed, which was further exemplified when credit rating agencies decided to give the whole MBS system the highest possible safety rating (AAA, to be precise).

With the number of people wanting their hands on MBSs, financial organisations realised that the only way to cope with the demand, as well as maximise their profits in turn, was to increase the number of people who were eligible to buy a house. This led to the introduction of sub-prime mortgages, which were mortgages loaned to people who had a low income and poor credit score, and were unlikely to repay the loan on time, or even at all. This directly contrasts what was stated in the beginning: why would lenders put themselves at risk of high defaulting? Once again, this was to exploit the increased prices of real estate. If a low income person was unable to repay the full loan, firms would then take ownership of the house and put it back on the market for a high cost and with high appreciation opportunities. Regardless of whether or not the person would repay the loan, banks and fiscal organisations found themselves making more money at the end of it all. This seemed like such a great breakthrough, that even traders jumped on the bandwagon and started loaning their own MBSs, called Collateralized Debt Obligations, or CDOs, which were also given the AAA rating.

The reality was that these "mega-mortgages" were actually extremely risky, something which went unnoticed given the immediate, short term successes of the scheme. As expected, defaulting reached an all time high, with more houses re-emerging on the market again. This also plunged a lot of people already on low incomes into further financial distress. The not-so-great news was also delivered to the doorstep of many large banking firms: whilst more houses were on the market again, more people had also already taken large loans (thanks to the high rate of MBS distribution) and were not prepared to buy another house. Supply went up, demand went down, and soon, prices of real estate properties went underground. Furthermore, investors who spent a fortune on MBSs quickly discovered the ugly truth that the whole scheme was going downhill and that they were unlikely to make back the money they spent.

There's another player in this field of financial devastation, and that is the insurance firms. More specifically, it was the unregulated dishing out of derivatives, which are (simply put) financial contracts who's value comes from, or is derived from, the value of an asset, like a house. There are several types of derivatives, though the one which is of utmost significance here is the Credit Derivative Swap, or CDS, which is essentially insurance which compensates a homeowner should they find themself being unable to repay the entire loan, and losing their home to defaulting. This was a pretty big deal, with companies such as the American International Group selling over tens of millions of dollars worth of CDSs. With the increased and unexpected rise in defaulting, companies like AIG resorted to covering the debts and losses of several parties, ultimately turning what was once a bet-like deal into a money draining machine.

With banks having loaned too much money and not being able to make that money back, let alone a profit, some major banks ended up making drastic losses and declaring bankruptcy. One such casualty was the downfall of Lehman Brothers, a company that once held up to $600 billion worth of assets. With the fall of several other banks looming, the Federal reserve and government launched the Troubled Assets Relief Program, which involved giving $700 billion to banks to prevent further financial havoc; in 2010, President Obama signed the Dodd-Frank law to control the distribution of loans and derivatives.

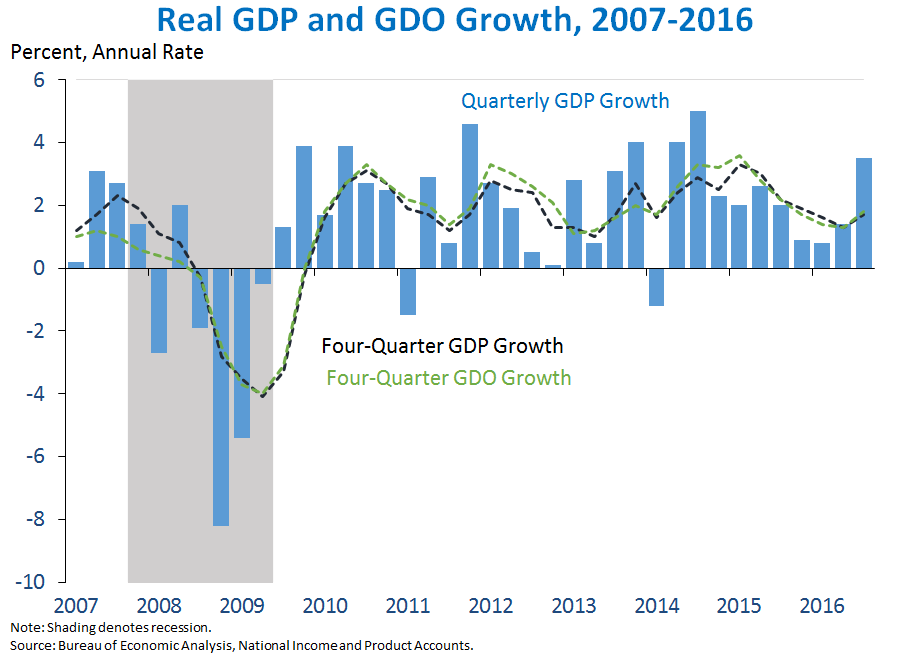

So what were the underlying effects of the economical crisis? It's one thing to understand the history and causes of the recession, but lest we forget the effects on the people and the economy. What better way to demonstrate this but with yet another graph?

From the graphs above, we can see an extremely significant and clear fall in the GDP across the world, but more interestingly several fluctuations in the GDP ever since, perhaps suggesting how fragile the economy has been ever since.

Naturally, as banks went under, so did the people working for them. As illustrated by the graph. unemployment in the US, arguably where the crisis began, reached 10% of the population from just 4.6% a few years before. It took almost 8 to 9 years after that for the level of unemployment to reach the pre-recession standard.

Overall, the financial crisis of 2008 was a historical economic disaster that has left its mark on the global banking world, as well as families that have lost their livelihoods as a result of either not being able to repay a mortgage, or not having a home to live in, or not having a source of income, or (for a lot of people) all of them. It's something that is still being studied extensively today, a complex conjecture that seems to have no clear end or pattern. Just goes to show the volatility and unpredictability of the world of economics.

Comments

Post a Comment